Your Website Is Your Passport

One of the themes that crops up again and again in the IndieWeb community is that your personal domain, with its attendant website, should form the nexus of your online existence. Of course, people can and do maintain separate profiles on a variety of social media platforms, but these should be subordinate to the identity represented by your personal website, which remains everyone's one-stop-shop for all things you and the central hub out of which your other identities radiate.

Part of what this means in practice is that your domain should function as a kind of universal online passport, allowing you to sign in to various services and applications simply by entering your personal URL.

This is actually pretty easy to get working on your own website. Considerably less easy is understanding the underlying protocols and mechanisms on which it relies. If that topic interests you, you'll find much more information in the latter half of this article, presented in a manner that I hope is not too inaccurate.

For the Impatient

The simplest (though not the only) way to leverage your website for sign-in purposes is to delegate the authentication process to an existing social media profile.

First, add a special "me" anchor tag to your home page detailing where to find the profile you want to use. Let's say, for the sake argument, that you want to use your Github account. The link would look like this:

<a href="https://github.com/drivet" rel="me">Github</a>Note that there is nothing special about this link, aside from the "me" attribute. You can use it like any other link on your home page. Obviously, replace the "drivet" part with your own username.

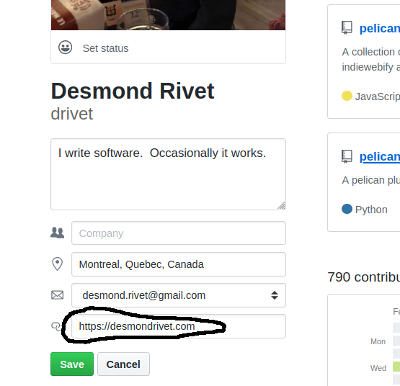

Next, edit your Github profile so that the website field points back to your root domain. You do this to show that you actually control the Github account to which your homepage is pointing:

Finally, add this link tag to the head of your homepage:

<head>

....

<link rel="authorization_endpoint" href="https://indieauth.com/auth">

</head>You should now be able to sign in to, for example, a website like indieweb.org. You can try it now by going to the site and clicking the "Log in" link.

You'll be presented with a text box into which you can enter you personal domain. The service to which you're trying to authenticate (i.e. indieweb.org) will outsource the process to the authorization_endpoint link it finds embedded in your homepage. The particular endpoint we've set up will look through your homepage and delegate the actual authentication procedure to the first "me" link it finds. In our case, we will be asked to log in to Github, or we will be informed that we are already logged in. Obviously, if you use this procedure, you are still dependant on an external service (indieauth.com) coupled with an existing social networking profile (Github), which is less than ideal, but at least the authentication process starts on your own domain, and there are ways to detach yourself from your external profiles completely if you wish to go that far (see, for example, the selfauth project).

Please note that what I've just described is an authentication procedure. It's enough to get you logged in to services which support the protocol. It is not, by itself, an authorization procedure which means you won't be able to use something like Quill (a Micropub client) out of the box. For that to work, you need to obtain an access token after authenticating. Luckily, that's pretty easy to do as well if you're willing to rely on an external service. Just add the following link to the head of your website:

<head>

....

<link rel="token_endpoint" href="https://tokens.indieauth.com/token"/>

</head>Once again, if using an external service bothers you, you can host your own token service.

And that's pretty much it. Easy, right?

For the Less Impatient: A Brief Detour Into OAuth-land

The process of using your domain to log in to sites and services is called web sign-in and is implemented via a protocol called IndieAuth, an extension of OAuth used for decentralized authentication.

(When I speak of "OAuth", I refer to OAuth 2, not OAuth 1. OAuth 1 is rarely used nowadays, and is therefore not pertinent to this discussion)

The specific process used by the indieauth.com service, whereby it looks for a rel="me" link on your homepage and then delegates the actual authentication procedure to that service link, is called RelMeAuth and is a popular way to implement IndieAuth, though not the only one. The selfauth project, for example, implements a simple self-hosted password scheme.

Understanding IndieAuth requires a basic knowledge of OAuth, which is a daunting subject if you've never dealt with it before (and even if you have). I'm going to try and give just enough information here to illustrate where IndieAuth fits into this landscape, but if you want more information I highly recommend reading the resources at oauth.com; I find they strike a good balance of detail, especially if you have a modicum of programming and HTTP experience.

What Problem Does OAuth (Not) Solve?

The "auth" in OAuth stands for authorization, not authentication and, accordingly, OAuth is an authorization protocol, not an authentication protocol. What this means is that OAuth is fundamentally about managing access to online resources (like REST APIs) and not about the identity of the user whose resources are being accessed.

The example often given is that of a printing application A that wants prints photos from a photo sharing application B, where both applications are managed by different business entities. In the past, a problem like this may have been solved by configuring your credentials for B somewhere in A, but that has several issues, not the least of which is that A now has full access to your entire account in B, even though all it needs to do is print out a few photos.

OAuth is designed to help with this problem. It's meant to allow you to give applications limited access to resources from another service without having to give away your full credentials. It does this by issuing tokens representing the resources the application wishes to access, along with the actions the application is allowed to take on those resources.

The concept of a token here is not unlike the concept of hotel room access card. The access card lets you into your own room, but it doesn't grant you access to the entire hotel; you can't use it to go into another room, for example, and you certainly can't use it to go into the staff areas.

OAuth's Moving Parts

The OAuth spec defines several actors:

- The end user, or the one who owns the resources. In the above example, that would be the person who is trying to print their photos.

- The client or the application acting on behalf of the user. This would be the printing application (A) in the above example.

- The resource service. This would be the photo sharing service (B).

- The authorization server, existing alongside the resource service. This manages the actual OAuth protocol. In practice this is almost always managed by the same business entity as the resource server, though the spec explicitly allows different configurations.

The central idea behind OAuth is that the end user delegates resource access to the client application, so that the application can access the resources on the user's behalf. The final result of this delegation process is the access token, an opaque string that is meant to be included in the API calls via the HTTP Authorization header:

GET /api/blah Authorization: Bearer 128728364872

Before any of this can take place, the authorization server requires a priori knowledge of the client attempting to access the resource. To use the ongoing example, the authorization server associated with the photo sharing application (B) needs to know, ahead of time, that the printing application (A) may be accessing the photos. This is usually accomplished via an explicit, out of band client registration step occurring before any authorization takes place. Among other things, a client id needs to be provided so that the authorization server is able to recognize who's asking for what.

From Authorization to Authentication

OAuth's access tokens are comparable to hotel access cards and the simile is a pretty good one. Your card grants you access to your room, and maybe some of the common areas, but not the whole hotel; other people's rooms remain off limits, as do the staff areas. We could say that the access card authorizes you to enter you room, but not much else.

It's worth noting, however, that your name and photo are not on the access card. Your access card isn't a piece of identification. If it were stolen, the thief would have no trouble ransacking your room. Someone who stole, say, your driver's licence, on the other hand, would have a hard time using it as such because their name and face don't match what's on it.

When we say that OAuth is an authorization protocol rather than an authentication protocol, this is part of what is meant.

And yet, even so, there are subtleties at play here that are understandably confusing. The process of obtaining your hotel access card, for example, will almost certainly involve an authentication step - you'll probably have to show, say, your passport or driver's licence to the clerk at front desk. In the same vein, and pretty much for the same reason, the OAuth protocol does (usually) include one or two authentication steps before the token is issued.

This leads some people to conclude that plain vanilla OAuth can be used as an authentication protocol and they're almost right, but not quite. There are several issues with trying to do this, but the main problem is that authentication protocols are generally expected to produce the identity of the end-user after the authentication procedure successfully completes and there is absolutely nothing in the OAuth spec which would allow an implementation to do this out of the box. The whole point of the OAuth process is to obtain an access token, and access tokens are meant to be opaque strings; there's no standard way to know the identity of the user involved in the creation of the token. Indeed, depending on which flavour of OAuth you use, tokens may be granted with no end-user authentication at all.

The point is that unvarnished OAuth leaves too many blanks to function as an authentication protocol on its own. That being said, it is, of course, eminently possible to fill in those blanks and create an authentication protocol by extending OAuth, but any such extensions would necessarily fall outside the OAuth spec.

From OIDC to IndieAuth (Finally!)

The obvious question to ask, at this point, is why no one has created a standard authentication extension to OAuth. This question has an obvious answer: of course people have done exactly that! One of the more well-known examples is OpenID Connect (OIDC); it's the protocol behind all the "Sign in with Google" buttons sprinkled around the Internet. It extends OAuth in many ways, one of which involves defining a standard token format which can be used to glean information about who's trying to login.

OIDC is very much about authentication and it is very much built on OAuth but, despite the name, it doesn't actually have that much in common with the now dead OpenID protocol. Typical usage of OIDC requires some kind of pre-existing arrangement between the service needing sign-in capabilities and the identity provider. In other words, the service needs to plaster a "Sign in with Google" button somewhere on their website. Those who want to sign-in with another OIDC provider X won't be able to do so, unless the application explicitly allows it by adding another "Sign in with X" button.

OpenID, on the other hand, was a portable identity management system and a truly decentralized authentication protocol. You chose an OpenID provider, and you were provided with an ID in the form of a URL. This ID could be used to log in to services which supported the OpenID protocol, even if the service didn't know about your OpenID provider beforehand. The IDs were also portable; you could change providers without changing ID. It was similar in concept to a cell phone number.

Sound familiar? Sounds a lot like IndieAuth, right? It's not a coincidence; IndieAuth is considered something of a spiritual successor to OpenID.

IndieAuth is built on OAuth but extends it in several ways:

- Client ids and user ids are explicitly defined as resolvable URLs.

- The typical client registration step associated with OAuth is avoided by recognizing that client ids and users ids, being resolvable URLs, are already implicitly registered in DNS.

- Client and user information are extracted from their respective URLs by taking advantage of microformats.

- The specific authorization and token endpoints used in the IndieAuth protocol are discovered via the user's homepage, located at the URL provided at the start of the process.

IndieAuth is a thin, decentralized identity layer on top of OAuth. It's entire reason for being is to answer the simple question: does the person behind the browser have control over the URL that they are claiming as their own?

In that sense, IndieAuth is a much more modest protocol than OIDC, whose scope includes things like session management and standard user profiles. And yet, being a completely decentralized protocol, it's much more in keeping with the spirit of the IndieWeb. If your goal is to make a social network out of the world wide web, there is a certain elegance to the idea of leveraging DNS as a user registration system.

More to Come

This blog entry was much harder to write than I thought it would be. I tend to write in order to clarify and solidify my own understanding of a topic and, in all honesty, I did not find OAuth a particularly easy subject to grasp. I do think I have a better handle on it now and I'm going to once again recommend the resources at oauth.com, especially if you know a programming language. They take you through the process of writing a very simple OAuth server and it's enlightening.

There's a lot more to write about the IndieWeb, and I'm planning on publishing at least a couple of more blog entries (probably revolving around webmentions and microformats, but we'll see). Stay tuned!

Post a Comment