On Pulling Musical Notes Out of Thin Air

I am an unapologetic Downton Abbey fan. The series is full of memorable scenes, but one in particular has stuck with me. Daisy, one of the scullery maids, is asked if she turned on the electric lights in one of the rooms and she replies "No. I daren't".

It seems like such a minor, throwaway line, but I feel like it succinctly captures how the uninitiated must have felt about electricity back then. Daisy is downright afraid of it. Steam and fire are very direct and literal sources of energy, but electricity is much more abstract. You never see the electricity moving or burning, even as the motor spins or the lamp shines.

It must have seemed rather ghostly. Spooky, even.

And the idea that one could make music from this stuff - that one could build a device to turn this abstract, invisible force into something audible and pleasing to the ear - must have been downright unnerving.

Music from the Void

People often assume that electronic musical instruments were invented in the 1960's with the advent of the synthesizer, but that's not quite not true. The world's first electronic musical instrument actually predates the synthesize by a good 40 years. It's called the theremin and it certainly qualifies as one of the most unusual instruments ever invented. To my knowledge it is the only musical instrument that one plays with no physical contact.

Even if you've never heard of a theremin, you've probably heard one being played without realizing it. You know that high-pitched twang from a typical 1950's sci-fi movie? That's a theremin in action. Because it was typically used for these kinds of soundtracks, people came to associate it with eerie, spooky situations (which I feel is somewhat appropriate, given the eerie, spooky nature of electricity itself).

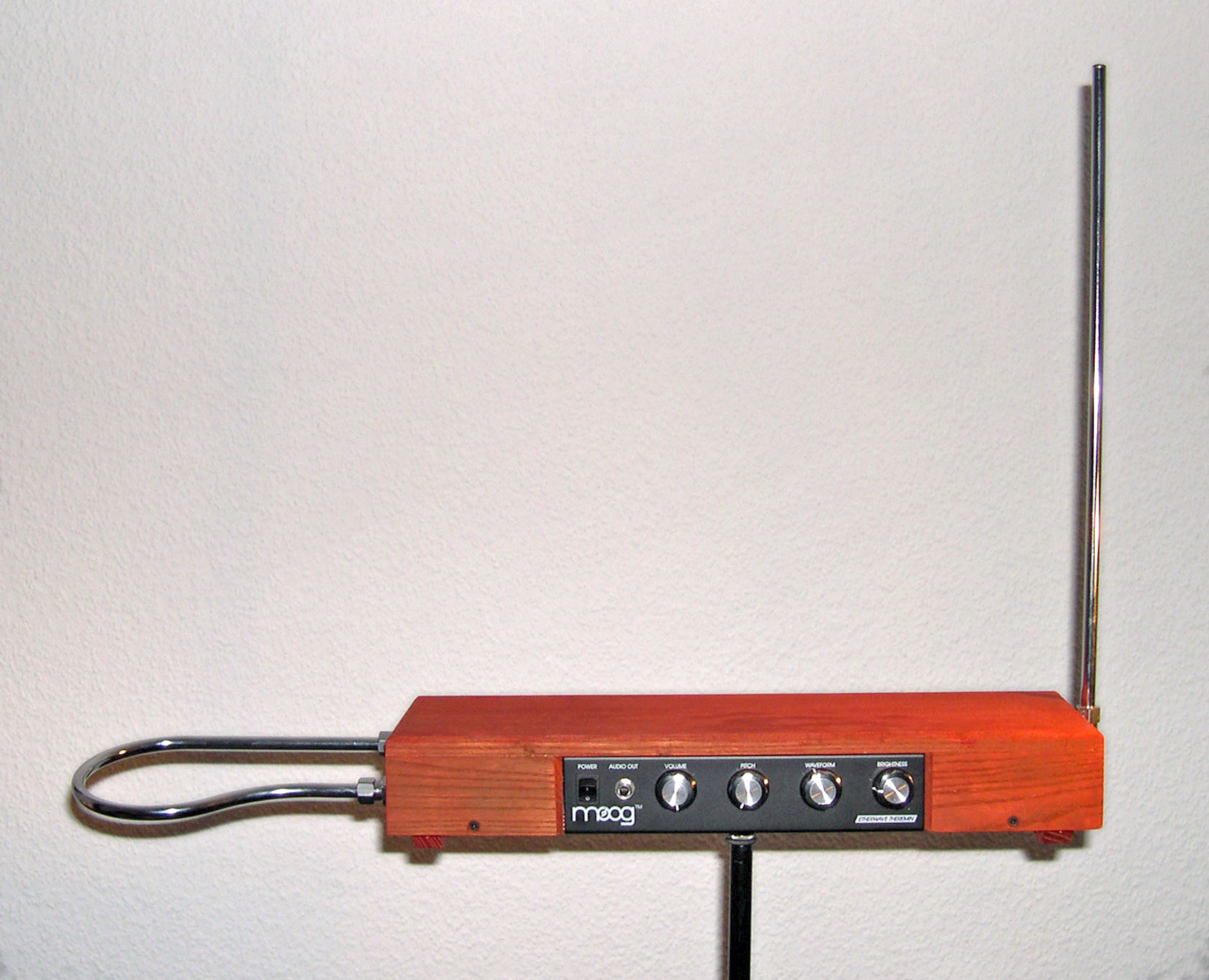

The instrument consists of two metal rods (usually called "antenna", though they operate on different principles). One of the rods is usually pointing in the air, and the other is usually curved in a loop. One controls the pitch by moving one's hand to and from the first rod; the closer one's hand, the higher the pitch. The second antenna controls the volume in the same way; moving your hand closer lowers the volume. A typical setup looks like this:

Given the lack of anything physical to manipulate, they are notoriously difficult to play. They are also the butt of many jokes. For example:

In the right hands, however, they are very, very cool. Don't believe me? Consider exhibit A. She starts playing the theremin around the one minute mark but you should watch the whole thing :

I'll be honest, this video, more than any other, makes me want to learn to play.

Basic Principles

From a cultural and musical standpoint, theremins are fascinating devices. They are also fascinating from an engineering standpoint.

Internally, for each antenna, one constructs an electronic oscillator out of capacitors and inductors. The frequency of the oscillator is a function of the particular capacitors and inductors used in the circuit. Each antenna forms one half of a capacitor, connected directly into its oscillator. The player's hand forms the other half; when their hand moves to and fro, the capacitance of the antenna changes, thus changing the frequency of the oscillator. Though this frequency is not in the audible range, theremins use a process called heterodyning, which basically consists of shifting the frequency onto the audible spectrum so that one may actually hear a note.

In other words, a theremin works because the player effectively forms a part of the circuit - one half of a capacitor. I don't know why, but I find that idea pleasing to think about.

Onward and Upward

Why am I writing about theremins? Well, one answer is simply that I like theremins, and that this is my blog and I'll write about what I darn well please.

Another answer, closer to the mark, is that they're great fodder if you're looking to tinker with hobby electronics. Stay tuned for more information on how far I got on that score.

Post a Comment